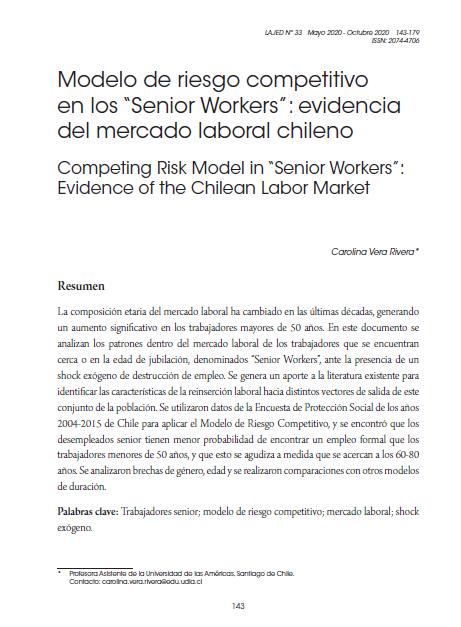

Competing Risk Model in “Senior Workers”: Evidence of the Chilean Labor Market

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35319/lajed.202033419Keywords:

Senior workers, Competing Risk Models, Labor markets, Exogenous ShockAbstract

The age composition of the labor market has changed in recent decades, generating a significant increase in workers over 50 years. This document analyzes the patterns within the labor market of workers who are close to or at retirement age, called “Senior Workers” in the presence of an exogenous shock of job destruction. It generates a contribution to existing literature to identify the characteristics of the labor reintegration towards different exit vectors of this group of the population. Data from the 2004-2015 Social Protection Survey of Chile were used to apply the Competitive Risk Model and it was found that senior unemployed people are less likely to find a formal job than workers under 50 years of age and that this is exacerbated as they approach 60-80 years. Gender and age gaps were analyzed, and comparisons were made with other duration models.

Downloads

References

Adams, S. (2004). Age discrimination legislation and the employment of older workers. Labour Economics, 11(2), 219-241.

Aghion, P; Algan, Y. y Cahuc, P. (2011). Civil Society and the State: fte Interplay between Cooperation and Minimum Wage Regulation. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(1), 3-42.

Albagli, E. y Barrero, A. (2015). Tasa de desempleo y cambios demográficos en Chile. Minuta anexa IPoM marzo 2015. Mimeo. BCCh.

Belloni, M. y Alessie, R. (2009). fte importance of financial incentives on retirement choices: New evidence for Italy. Labour Economics, 16(5), 578-588.

Benitez-Silva, H. y Ni, H. (2010). Job Search Behaviour of Older Americans, Mimeo.

Black, D. y Liang, X. (2005). Local Labor Market Conditions and Retirement Behavio. Working Paper Nº 2005-08, Boston College Center for Retirement Research.

Blake, H. y Sangnier, M. (2011). Senior Activity Rate, Retirement Incentives, and Labor Relations Economics: fte Open-Access. Open-Assessment E-Journal, 5 (2011-8), 1-32.

Blau, D.M. y Gilleskie, D. (2006). Health insurance and retirement of married couples. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 21(7), 935-953.

Boockmann, B; Fries, J. y Göbel, C. (2011). Specific Measures for Older Employees and Late Career Employment. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.2159817.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2000). Incentive effects of social security on labour force participation: evidence in Germany and across Europe. Journal of Public Economics, 78(1-2), 25-49.

Callaway, B. (2015). Job Displacement of Older Workers During the Great Recession: Tight Bounds on Distributional Treatment Effect Parameters Using Panel Data. Manuscrito inédito, Vanderbilt University, October.

Casey, B; Oxley, H; Whitehouse, E; Antoln, P; Duval, R. y Leibfritz, W. (2003). Policies for an ageing society: recent measures and areas for further reform. Economics Department, Working Paper Nº 369. OECD.

Chan, S., y Stevens, A. H. (2001). Job Loss and Employment Patterns of Older Workers. Journal of Labor Economics, April 2001, 19(2), 484-521.

Coile, C.C. y Levine, P.B. (2007). Labor market shocks and retirement: do government programs matter?. Journal of Public Economics, 91(10), 1902-1919.

---------- (2011). Recessions, retirement, and social security. American Economic Review, 101(3), 23-28.

Coy, P. (2014). American workers are older than ever. Bloomberg Business Week. Disponible en: http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-08-04/a-record-22-dot-2-percent-of-ofu-dot-s-dot-workers-are-55-or-older

Denton, F. T. y Spencer, B. G. (2009). Population Aging, Older Workers, and Canada’s Labour Force. Canadian Public Policy, 35(4), 481-492. University of Toronto Press. Recuperado en noviembre 22, 2018, de Project MUSE database.

Duval, R. (2003). The retirement effects of old-age pension and early retirement schemes in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department, Working Paper Nº 24.

Fetter, D. y Lockwood, L. (2018). Government Old-Age Support and Labor Supply: Evidence from the Old Age Assistance Program. American Economic Review, 108(8): 2174-2211.

Friedberg, L. y Webb, A. (2005). Retirement and the evolution of the pension structure. Journal of Human Resources, 40(2), 281-308.

García Pérez, J.I., y Sánchez Martín, A.R. (2012). Fostering job search among older workers: the case for pension reform. Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Working Paper Nº 12.09.

--------- (2013). Retirement incentives, individual heterogeneity and labor transitions of employed and unemployed workers. Labour Economics, 20, 106-120.

Gruber, J. y Wise, D. (2004). Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World: Micro Estimation. University of Chicago Press.

Hairault, J-O; Langot, F. y Sopraseuth, T. (2010). Distancetoretirementandolderworkers’ employment: the case for delaying the retirement age. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(5), 1034-1076, Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press, September.

Heckman, J. y Singer, B. (1985). Social science duration analysis. En J. J. Heckman y B. Singer (eds.), Longitudinal Analysis of Labour Market Data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Krueger, A., y Pischke, J. (1992). fte Effect of Social Security on Labor Supply: A Cohort Analysis of the Notch Generation. Journal of Labor Economics, 10(4), 412-437.

Lancaster, T. (1990). The Econometric Analysis of Transition Data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Li, Y. (2018). Paradoxical effects of increasing the normal retirement age: A prospective evaluation. European Economic Review, 101(C), 512-527, Elsevier.

Liebman, F.P; Luttmer, D. y Seif, G. (2009). Labor supply responses to marginal Social Security benefits: Evidence from discontinuities. Journal of Public Economics, 93(11-12), 1208-1223, ISSN 0047-2727.

Makarski, K. y Tyrowicz, J. (2017). On welfare effects of increasing retirement age. GRAPE Working Papers Nº 10, GRAPE Group for Research in Applied Economics.

Marcel, M., y Naudon, A. (2016). Transiciones laborales y la tasa de desempleo en Chile. Documento de Trabajo Nº 787, BCCh.

Martínez, C. y Vergara, R. (2018). Caracterización del mercado laboral para el adulto mayor. Puntos de Referencia, 492, octubre. Disponible en: https://www.cepchile.cl/cep/site/docs/20181031/20181031111549/pder492_cmartinez_rvergara.pdf

Matsukura, R; Shimizutani, S; Mitsuyama, N; Lee, S. y Naohiro, O. (2017). Untapped Work Capacity among Old Persons and fteir Potential Contributions to the ‘Silver Dividend’ in Japan. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing. 12. 10.1016/j.jeoa.2017.01.002.

Mealli, F. y Pudney, S. (1996). Occupational pensions and job mobility in competing risks model. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(3), 293-320.

Morrison, R. y Villagrán, M. (2014). Envejecimiento activo de la población chilena. Santiago de Chile: RIL editores.

Neumark, D; Burn, I. y Button, P. (2015). Is it Harder for Older Workers to Find Jobs? New and Improved Evidence from a Field Experiment. NBER Working Paper Nº w21669.

OECD (2015). Pensions at a glance. OECD Publishing.

Ramírez, S. (2018). Cambios en la composición etaria de la fuerza laboral y sus efectos en el desempleo: una aplicación para Chile. Tesis PUC.

Staubli, S. y Zweimuller, J. (2012). Does raising the retirement age increase employment of older workers? University of Zurich Department of Economics Working Paper Nº 20.

Tejada, M. (2018). Informalidad laboral en Chile. Observatorio Económico, 131, noviembre. Universidad Alberto Hurtado. ISSN 0719-9597.

Van den Berg, G.J. (2001). Duration models: specification, identification, and multiple durations. En J.J. Heckman y E. Leamer (eds.), Handbook of Econometrics, 5, 3381-3460. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Vigtel, T. (2018). fte retirement age and the hiring of senior workers. Labour Economics, 51, 247-270, ISSN 0927-5371.